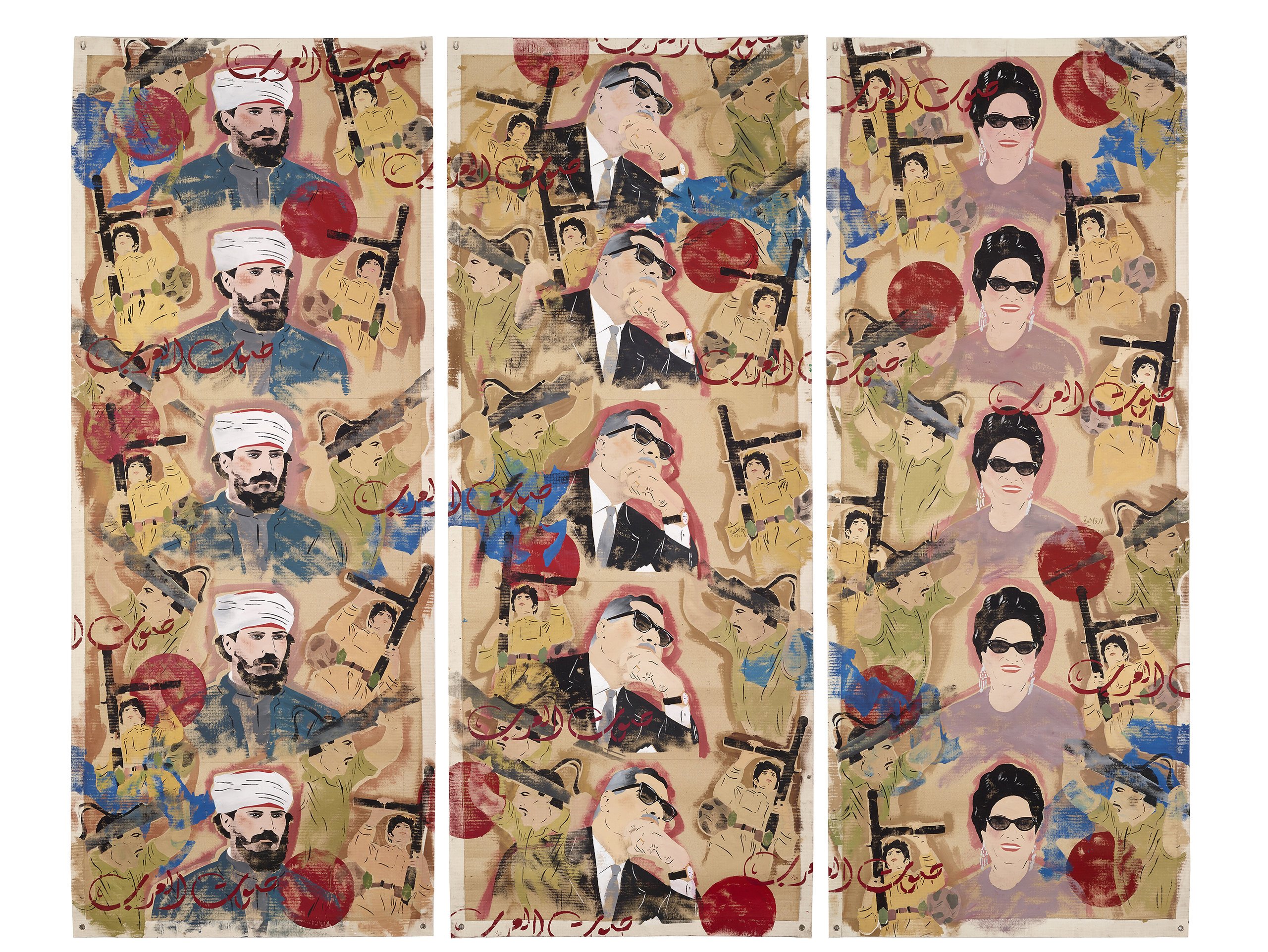

Sawt el Arab, 2008, Colour Pigments on Corrugated Cardboard, Hand-Colored Cotton Borders, 250 x 300 cm. Courtesy of the Dalloul Art Foundation.

For Chant Avedissian, art was always an act of resistance. “I do not do art,” he once declared. “I do fighting against influences.” Born in Cairo in 1951 to Armenian parents, Avedissian grew up between cultures, faiths, and languages. His life and work unfolded as a lifelong negotiation of belonging, an insistence on defining identity from within rather than accepting the hierarchies handed down by the West.

Educated at Montreal’s School of Art and Design and later at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Avedissian absorbed the tools of Western modernism, both to utilize and unlearn them. Returning to Cairo in 1980, he found his true mentor in the visionary Egyptian architect Hassan Fathi, accompanying him as archivist and photographer for nearly a decade. Fathi’s devotion to indigenous materials and vernacular craft freed him from what he later would repeatedly equate with ‘cultural abuse’ – the inherited conviction that Paris was the only center of art. As he once told writer Sadia Shirazi, he “had to clean what [he] had learned for thirty years,” relearning how to see through the adobe brick and the patterns of local artisans.

That process shaped a visual language rooted in material modesty and conceptual precision. From cotton textiles to corrugated cardboard, Avedissian’s chosen surfaces echoed the mobility of nomadic culture. The result was, without fail, works that could roll, travel, rearrange, and breathe. “The whole thing ends up in a box,” he said of Bedouin tents, a metaphor for art that refuses to ossify. His practice was an architecture of impermanence, a rebellion against the stillness of the museum wall.

You are Love, 2008, Gouache on Cardboard, 49 x 69 cm. Courtesy of the Barjeel Art Foundation.

Gamal Abd El Nasser, 2008, Gouache on Cardboard, 49 x 69 cm. Courtesy of the Barjeel Art Foundation.

His now iconic stencil works emerged from this ethos. What began in 1991 as a commission to reproduce a portrait of Umm Kulthum evolved into the monumental Icons of the Nile. The series of 120 painted panels reimagined Egyptian modernity through its most resonant “golden age” symbols and emblematic figures: the diva’s raised arms, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s meditative profile, the anonymous village girl, the brick of Fathi’s architecture. These images, printed on salvaged cardboard and layered with patterns drawn from Islamic, Ottoman, and Bedouin design, blurred the line between popular image and sacred icon.

As curator Rose Issa recalled in Selections, his work was never nostalgic. By reproducing state-media imagery from the 1950s and 60s – the very mise en scène of nationalism – Avedissian revealed its constructed nature. “The images said things about liberty and happiness and sports,” Avedissian has previously said, but everything was “composed, for propaganda”. His stencils, endlessly repeatable, were not simply portraits of a golden age but critical meditations on how that age was performed and remembered.

In works such as You Are Love and Gamal Abdel Nasser, the bold, flat planes of color and rhythmic geometric backgrounds recall both the propaganda poster and the devotional icon. Bent el Karia and Om el Sebian extend this lexicon into the everyday, celebrating women’s labor and tenderness as emblems of collective endurance. Meanwhile, Sawt el Arab collapses politics, culture, and myth: Kulthum and Nasser reappear beside Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, their silhouettes vibrating against a backdrop of marching figures. It is a poignant portrait of Arab modernity as both dream and disillusion.

Om El Soubian – Icons of the Nile 171, 1990-93, Gouache on Cardboard, 52.5 x 72.5 cm. Courtesy of Sabrina Amrani Gallery.

Bent el Karia – Icons of the Nile 153, 1990-93, Gouache on Cardboard, 52.5 x 72.5 cm. Courtesy of Sabrina Amrani Gallery.

Throughout, Avedissian positioned himself against Eurocentrism and its seductive myths. “It is child abuse when parents tell their children that Paris is the center of art,” he once said – half in jest, wholly serious. His lifelong injunction was to “look East”: toward Samarkand, Aleppo, Bukhara, and other nodes of a shared visual civilization too often ignored by Western art history. His practice made visible the transcontinental routes of pattern, form, and faith that long predated modernity’s borders.

Even at the height of his success, when Icons of the Nile sold for over $1.5 million at a Sotheby’s auction in Doha, setting a record for a living Arab artist, Avedissian resisted the machinery of the market. He avoided institutional exhibitions in Egypt and gave much of his earnings away. His legacy, stewarded today by curators such as Issa and Sabrina Amrani, stands not only in museum collections but in the stubborn clarity of his ethos: art as reconstruction, identity as craft, and vision as defiance.

Enduring as both archive and antidote, Chant Avedissian’s work is a map of the East drawn against forgetting. His art lives in the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Museum of African Art, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and beyond. But perhaps its truest home is still Cairo, where corrugated cardboard scrolls echo the hum of radio voices, and painted icons remind us that identity, like pattern, repeats to survive.